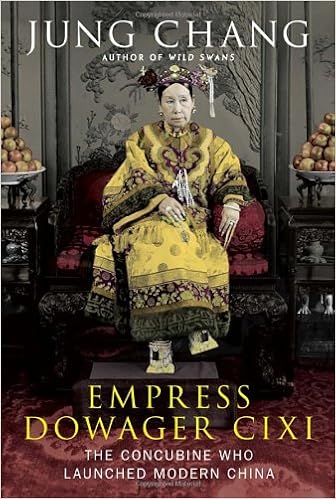

This week I'm talking about a fairly recent biography of Empress Dowager Cixi, or as she was known to contemporaries as the Empress Dowager of China. There may have been other people who held the title but as far as the rest of the world was concerned, she was the only one who counted. In this biography Jung Chang not only charts Cixi's life, from a low-ranking concubine of the Manchu Emperor to her eventual place as absolute monarch of the most populous country in the world, but the history of China in the nineteenth century. The two topics are so inextricably linked that it is impossible to talk about one without the other.

The importance of this biography, as Chang points out, is that Empress Dowager Cixi is an often maligned figure in history and already during her lifetime her name and legacy were greatly blackened. But as Chang illustrates through numerous primary sources, and the Imperial Chinese were extensive record-keepers, many of the accusations are either grossly inflated or absolutely unfounded. To be certain, Cixi was not a perfect individual and had quite a few faults of her own, and made a few very high-profile mistakes during her life, but they provide an incomplete picture compared to the whole person.

Cixi was from a prominent Manchu family and was actually relied upon by her father to help manage family affairs, giving her extensive experience most women didn't have at the time. Cixi was given the great honor of being selected as a bride for the emperor, but was originally a mere concubine and one of fairly low rank as well. Cixi would have meant a life locked away in the imperial harem, with little influence at court and regulated to the women's sphere. However, Cixi had the good fortune of bearing a son for the emperor, the all-important male heir. Although her son would be raised by the Empress, the emperor's official wife, Cixi had a good working relationship with the Empress and they both cared very deeply for her child. When their husband died in the aftermath of the Second Opium War, Cixi and the Empress became co-Empresses and actually worked together to topple a council of regents and have themselves installed as regents instead, although Cixi was far more interested in the actual business of government than her partner. Cixi would end up ruling off and on as Empress until the early 1900's, bringing about many reforms to China and helping to push it into the modern era.

Cixi is often depicted as a reactionary, trying to keep China embedded in its Confucian, hierarchical past and expelling foreigners from its shores. The truth couldn't be any more different. During the events of the Second Opium War, Cixi understood that the attempts to keep the Europeans out of China only made them more determined to force their way into the country. Furthermore, China's antiquated military, despite its considerable size, was utterly unable to even slow Europeans armed with modern arms and equipment. Cixi knew that if China, and more importantly the Ching Dynasty, were going to survive then China would have to learn from the West. During her reign, Cixi introduced numerous reforms to the country, beginning with a reform of the customs collection service, which greatly increased the state's income and allowed Cixi to fund her other projects. A modernized army and navy, the telegraph, electric lighting, railroads, overhaul of the Chinese education system, reformation of the legal code, and the abolition of foot-binding were all projects Cixi introduced to China during her years as Empress. Some met with more success than others, but it was a step in the right direction to make China the Great Power she knew it could become.

If Cixi was such a supporter of progressive reforms in China, why is she often looked upon as a vile reactionary a century later? Especially when there is extensive evidence to the contrary? Well the answer is complicated because there are numerous reasons. First, Cixi was fighting a lot of institutional inertia during her reign. The Chinese government was dominated by men educated in the classic Confucian texts which made them extremely resistant to almost any change. During Cixi's brief retirements when first her son and then later her nephew ruled as emperor in their own right, a large number of reforms Cixi undertook were rolled back by the conservative establishment. A second reason, as Chang points out, is that as a woman Cixi wasn't strictly allowed to rule in her own right as empress. Instead she was often acting as regent and working through a ruling council of men, making decisions in their name rather than in her own. The result is that most of the credit for Cixi's efforts go to the men who were taking orders from her, rather than Cixi herself.

Probably the biggest reason Cixi is labeled as a reactionary is because of her decision to side with the Boxers in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900. The Boxers were a popular movement who believed their skills with martial arts would make them immune to bullets and allow them to repel Europeans from China. As Chang illustrates, Cixi's alliance with the Boxers was one out of necessity. An alliance of eight western powers were sending troops to attack Beijing and with the Imperial Army in utter disarray, Cixi found herself dependent on an alliance with the Boxers to protect the capital. This was a decision she would later deeply regret for its unfortunate consequences. Cixi also made several poor decisions during her lifetime which would become ammunition for her detractors in later years. In a moment of weakness Cixi accepted lavish presents for her sixtieth birthday at a time when the country was at war and making extreme sacrifices. In addition, Cixi skimmed money from the navy's budget to help fund the restoration of the Summer Palace, a decision of definite moral dubiousness but the amount she embezzled was hardly the amount which later critics would attribute to her. Certainly these are excesses of royalty, but as Chang argues, not on a scale generally attributed to her.

Ultimately, Cixi was the victim of bad press in her own time, especially from Kang Youwei. Although Kang is often held up as a proponent of creating a constitutional monarchy or republic in China, Chang counters that Kang had less than honorable intentions and sought to put himself at the helm of China. When Cixi effectively banished him from China, Kang spent many years trashing the Empress in print and accusing her of a variety of excesses and misdeeds. Cixi never responded to these allegations because she believed they were beneath her and it would only be demeaning to respond to his attacks on her character. Unfortunately for history, Kang's story became the definitive version of events and Cixi became infamous as a result.

As I was listening to this book, I was unable to check the sources so I cannot say definitively how well-researched Chang's book has been. Doing a quick search I've been able to see there has been a great amount of debate as to whether or not Chang takes a completely impartial view of Cixi, veering somewhat into overly laudatory praise of the Empress Dowager, which definitely came through in the book. However, the utilization of primary sources to back up her arguments makes the book an interesting challenge to long-held assumptions if nothing else. Overall I'd recommend people take a look for themselves and see what they think.

- Kalpar

No comments:

Post a Comment