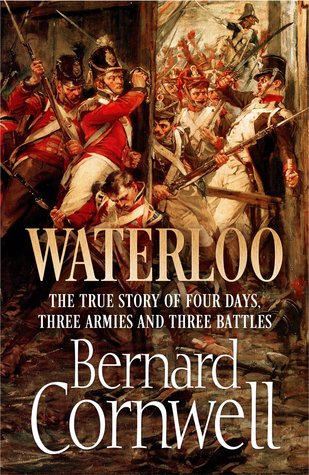

This week I'm taking a look at another book about the historic battle of Waterloo, in this case a book from historical novelist Bernard Cornwell. Before I get into the review I should preface this by saying that although Cornwell is the creator of the famous Sharpe series and does write a novel in which Richard Sharpe fights at the Battle of Waterloo, this book is not a historical novel. Instead it is a historical text, albeit somewhat short, in which Cornwell makes use of his considerable research to talk about one of the most studied battles in history. Cornwell himself somewhat undermines his book in the preface by stating that the subject of Waterloo's been studied numerous times and there have been perhaps countless books written on the subject before. However Cornwell argues that because Waterloo is such a fascinating battle he believes retelling the story is well worth the effort.

Inevitably, I am going to be contrasting Cornwell's work with the book written by Hamilton-Williams which I reviewed some time ago. One of the biggest contrasts I saw was that Hamilton-Williams puts a large amount of emphasis on the scale model of the Battle of Waterloo which he asserts has greatly influenced historical interpretation of the Battle in the years since. Cornwell mentions the model towards the end of the book and says Wellington believed it actually overstated the importance of the Prussians at the battle. But Cornwell points out that by the time the model was created Wellington had soured somewhat and so was willing to downplay the achievements of his erstwhile allies and take all the credit for winning the battle for himself.

In the key historical points Cornwell and Hamilton-Williams are in agreement, and it's very difficult to argue those anyway. Napoleon and his armies managed to defeat the Prussians at Ligny and fought the British, Dutch, and German forces to a draw at Quatre Bras on the same day, with one of Napoleon's corps marching between battles all day and playing no part in either. The Prussians, under Gebhard von Bluecher withdrew to Favre in the north with an intention of linking up with Wellington rather than retreating east back towards Prussia. Wellington also withdrew to the north, his position at Quatre Bras now exposed on two fronts, and took up a defensive position on a ridge south of the village of Waterloo which would allow Bluecher to join him, concentrate, and then fight Napoleon with a distinct numerical advantage.

On 18 June, 1815, Napoleon joined Marshal Ney's forces, who attacked Wellington's position on the ridge while Marshal Grouchy, under vague orders from Napoleon, marched towards Favre and engaged with the Prussian rearguard, a battle which he eventually won. However instead of tying down the entire Prussian army, most of it managed to march through back roads and eventually joined Wellington's forces in the afternoon, drawing off Napoleon's much needed reserves and eventually giving the allies the numerical advantage necessary to win the battle.

The main argument then comes as to why the allies won and Napoleon lost. Napoleon and many other French sources have long blamed Marshal Grouchy and other of Napoleon's subordinates who did not follow his orders properly. The standard British school of thought has given the lion's share of credit to the British and the King's German Legion forces there, while the other allies present have supported their own countries. And of course the Prussians, led by Bluecher's chief of staff Gneisenau, have stated the entire battle would have been lost without the Prussian contribution. The truth, as Cornwell states is somewhat more complex and for the most part Cornwell says we probably will never know the exact truth. The metaphor of a ball, apparently once used by Wellington, is repeated often in the book. Everyone will remember what happened to them and what they saw, but they will not have been everywhere and have seen everything. Everyone's individual account will vary depending on their location and their own opinions and memories. Some general facts may be agreed upon, but the specifics will be far more difficult to sort out.

For the most part, I think Cornwell does a good job talking about the whole story, keeping in mind the entire time that people's perspectives will of course be rather limited or downright wrong, especially on an early nineteenth century battlefield where the noise and smoke making seeing a few yards in front of you difficult and anything beyond that almost impossible. Cornwell works to incorporate a number of sources, although his perspective from Wellington's army is almost entirely British and only rarely mentions the Dutch, Belgian, or German allies. However, Cornwell does state that in their accounts the British charge their allies with cowardice, and the other allies charge the British with cowardice so the truth is they probably all performed admirably. However he does suggest the Dutch, Belgian, and German troops, who were more likely to be raw recruits compared to their British allies, were more likely to break, which suggests a slight hint of bias.

If there is any reason why Napoleon lost at Waterloo, Cornwell blames it on a combination of Napoleon's decision to wait until the ground was dry for use of his artillery, his decision to assault Wellington head on which only played to Wellington's strengths, his ambiguously worded orders, and some of Marshal Ney's decisions, who was making a very bad mess of things that day. Cornwell also states unambiguously that the Prussians arrived in time to help Wellington, whose army was at the breaking point, win the day and drew off much needed troops from Napoleon's reserves. Perhaps more importantly the Prussians, despite marching since the previous night, continued the pursuit of the French and ensured the complete destruction of Napoleon's army in the following night. If Cornwell's account is from a largely British perspective, it at least seems a rather even-handed if somewhat brief account of the battles.

I think my only strong complaint would be Cornwell's decision to, at points, move the narrative into the present tense. This is only a temporary decision and it's usually done at chapter breaks to ''catch the reader up'' so to speak on events that are happening on the battlefield when we rejoin the narrative. It just seems weird to me, personally, to shift between tenses like that and it's not something I've run into in other historical texts. I think that may be the historical novelist in Cornwell coming out during the book.

Overall, this book is pretty good, if rather brief. It gives a nice overview of the battle and at least gives credit to both the British and Prussians at Waterloo, if perhaps once again the Dutch, Beligians, and other Germans are getting the short shift. It's certainly not as detailed as Hamilton-Williams work, but I think it manages to avoid the pitfalls that other book tends to fall into. And certainly Cornwell has done enough research on the subject matter.

- Kalpar

No comments:

Post a Comment