So as promised, here is my review of

Around the World in Eighty Days by Jules Verne, first published in 1873. What makes this novel unique for Jules Verne was it lacked in the more fantastical elements of his other works, such as

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and

Journey to the Center of the Earth. However it is one of Verne's more famous books and has inspired numerous people to travel across the world and attempt to beat the record. The first person to do so was female reporter Nellie Bly, working for the

New York World in 1889. Ms. Bly managed to complete the journey in 72 days, proving that such a feat was possible. (Special thanks goes to my friend fuzzypickles for reminding me about Ms. Bly.)

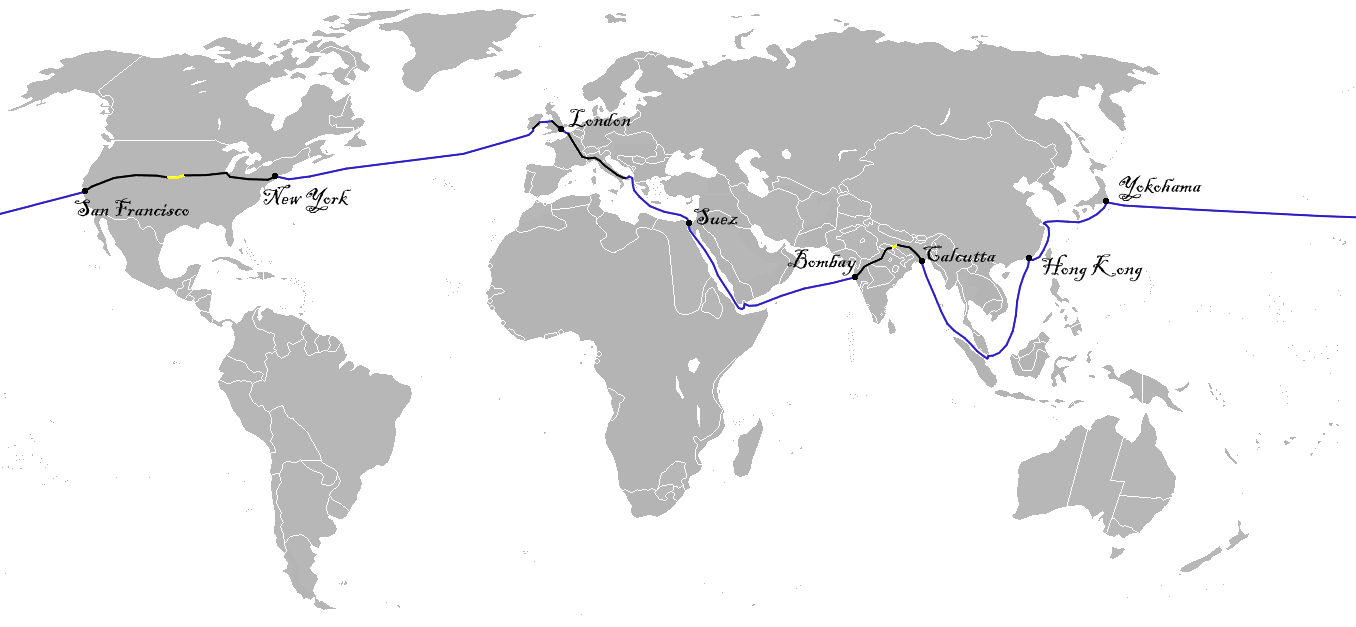

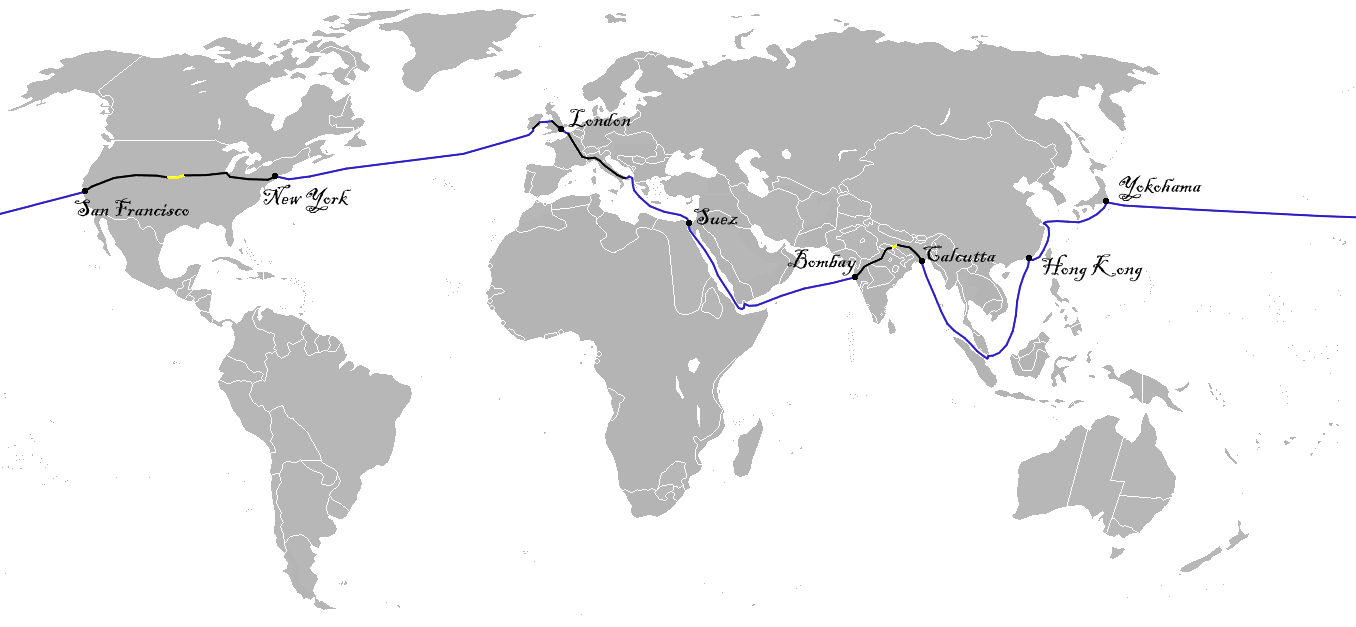

To the twenty-first century reader the challenge of crossing the world in eighty days seems unremarkable. With daily intercontinental flights by numerous companies across the globe, it's possible to cross the world in less than eight days, never mind eighty. However, it is important for a twenty-first century audience to remember the time period in which this book was written. It was the combination of a number of recent developments, intercontinental railroads, the Suez canal and regular oceanic steamship travel which enabled such a feat to be undertaken. It proved that the world, which previously could have taken a year to travel by ship, could now be done in a quarter of the time. In a way the world had shrunk as well. Raw materials from Africa and India would be used in Europe and shipped back as manufactured goods. News could travel by telegraph across the United States in a matter of minutes rather than days. Eventually people from places as far off as Australia and Kenya would find themselves fighting in a war over the assassination of an Austrian Archduke. In a way,

Around the World in Eighty Days is a harbinger for the global market and political stage of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Now I'm sure my readers are sitting down and saying, "Oh well that's all very well and find, but Kalpar! What is this book really about?" Well I would first respond by saying that it's about a group of people who travel around the world in eighty days. After you stopped punching and yelling at me, I would explain it is more specifically about the attempts of an English gentleman, Phileas Fogg, and his French valet, Passepartout to circumnavigate the globe in eighty days. Mr. Fogg is an extremely meticulous gentleman who operates like clockwork, leaving his house at eleven thirty every day and returning at midnight. His only activities consist of going to the Reform Club and playing cards with his gentleman friends. It is during one such card game that they discuss the possibility of traveling around the world within eighty days. Phileas Fogg, because he likes a challenge, wagers half of his fortune that he can perform the act and sets off immediately. Fogg and Passepartout run into a number of adventures along the way, mainly because of Mr. Fix a detective of Scotland Yard. Mr. Fix pursues Fogg across the globe because Fogg matches the description of someone who stole a considerable sum of money from the Bank of England and puts numerous obstacles in Fogg's way. Fogg and Passepartout also rescue a woman named Aouda during their adventures in India and she follows her rescuers as they continue around the globe.

|

| Map of their route taken from Wikipedia. |

The book also offers intriguing glimpses of the British Empire and America from an outsider's perspective, although being a nineteenth century novel it makes numerous generalizations on various nationalities. Regardless I find it a great window into the late nineteenth century world ranging from Europe to Japan, if only from a historical perspective.

Sadly, as a novel, I feel like the book failed to engage me. Phileas Fogg as a character is described as utterly devoid of emotion and so little remains known about him that I had a hard time connecting to him as a character. As the deadline for completing the race draws closer and closer and the remainder of Fogg's fortune continues to dwindle I feel...nothing. The book itself describes Fogg as little more than a robot, at least as far as the narrator and other characters are concerned. If he's worried about losing what's left of his fortune, the reader is given no sign so I find it almost impossible to become emotionally invested in him as a character. Passepartout, who I have to admit is the chief cause of numerous setbacks on their journey, is at least a character and gets emotional over their advantages and setbacks. As for the romance between Aouda and Fogg it feels practically forced. Yes, Fogg helped rescue her from a religious sacrifice and has seen to her every need from that point but the book describes Fogg doing this in an automatic fashion. When someone's as emotionally distant as Fogg it's usually hard for anyone to become emotionally attached to them so Aouda becoming infatuated with Fogg seems odd to me. Granted this is no better than my opinion but whatever.

Ultimately unless you're really really interested in reading about the nineteenth century, I'm going to have to suggest passing this book by. I felt like the characters lacked a certain depth and it was very hard for me to get invested in the race against time. Finally there's a plot hole that kind of bugs me at the end, so I'll go ahead and spoil it because the book's over 100 years old so you can't yell at me for that.

Okay, so as my readers may know, out in the middle of the Pacific Ocean is the International Date Line.

|

| This motherfucker right here. |

For those of you unfamiliar with the IDL, basically it separates today from tomorrow and how it makes it possible for me to be writing this article on a Friday evening while my friend in Liverpool, England is for some reason awake at 4:13 in the morning on Saturday. Prior to the nineteenth century human transportation wasn't fast enough for time zones and the date line to matter much, but with the advent of steam-powered transportation trains suddenly could arrive before they left. As a result the world was divided into twenty-four different time zones each representing twenty four hours of the day, however except for one hour the entire world is going to be split between two days. To make this entire mess somewhat tidier they invented the International Date Line which divides the use of two calendar days on the earth. Anyway, if you cross the line from east to west, for example traveling from the United States to Tokyo, you add one day to the calendar and jump forward to tomorrow. However, if you travel from west to east, departing China and heading for Mexico, you subtract one day and repeat yesterday.

The reason I go through all of this is because Fogg and company cross the Date Line on their travels and end up being able to meet the deadline because they gained an extra day crossing the line. Now while the International Date Line would not be established until

after when the novel is supposed to take place, it was at least informally in effect. Now Fogg and company aren't really affected by this during their journey in America because the trains leave on a daily basis but the ship they were supposed to take from New York to Liverpool left on a specific date and the book clearly states they miss the ship by fifteen minutes. Except if they gained a day, which is what saves them in the end, shouldn't they have arrived in New York a day early? I wouldn't make such a big deal if it wasn't the plot point that saved them in the end of the novel.

Ultimately I like this book for its historical value but otherwise it's unremarkable as a book in my opinion. If you really want to see this adventure I'd suggest looking at one of the many adaptations of the book into movie form.

Except for this one. This one's just dumb.

- Kalpar.

This week I've decided to delve back into the realm of incredibly old-school science-fiction by reading some Jules Verne. In this installment I've read two stories: From the Earth to the Moon, a story which details the creation of a giant cannon to launch a projectile at the moon and its eventual firing, and its sequel Around the Moon, which follows the misadventures of said projectile. Both of these stories are contained in one e-book available for free on Amazon.com. (However, I'm sure there are plenty of other places where you could obtain a copy as well.)

This week I've decided to delve back into the realm of incredibly old-school science-fiction by reading some Jules Verne. In this installment I've read two stories: From the Earth to the Moon, a story which details the creation of a giant cannon to launch a projectile at the moon and its eventual firing, and its sequel Around the Moon, which follows the misadventures of said projectile. Both of these stories are contained in one e-book available for free on Amazon.com. (However, I'm sure there are plenty of other places where you could obtain a copy as well.)