As my two readers probably know, I love history. As a result I occasionally like to read books about history and picked up Sacred Ties, by Tom Carhart, several months ago in a bargain book bin at my grocery store. More recently I got around to actually reading Sacred Ties and decided that I should share my opinions on it to my lovely readers. "But, Kalpar!" my readers are probably exclaiming at this point in time. "Isn't it most unusual for you to talk about history books on your blog?" Well....yes...but it's a thing I want to do so I hope you'll indulge me.

Sacred Ties follows the Civil War careers of six West Point graduates, George Armstrong Custer, Stephen Dodson Ramseur, Henry Algernon DuPont, John Pelham, Thomas Lafayette Rosser, and Wesley Merritt. According to Carhart all six were friends during their time at West Point, despite coming from all parts of the country, and were closer than brothers. However as the Civil War broke out in 1861 these six West Point Brothers found themselves on opposite sides. Custer, DuPont, and Merritt all became Union officers while Ramseur, Pelham, and Rosser all resigned from the US military to join the Confederacy. All six ended up serving in the Eastern Theater of the Civil War and witnessed the constant battles in Virginia and Maryland between the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

Overall I have a rather low opinion of this book and I'll try to explain it as well as I can. The first comment I want to make is that Tom Carhart gives General George McClellan a thorough lambasting in his book, with which I disagree. Carhart complains that McClellan is utilizing eighteenth century tactics on a nineteenth century battlefield and refused to ignore his own casualties to crush Lee early in the war. I find his hatred of McClellan unfounded on two main points. The first point is that throughout all of the nineteenth century generals continued to use mostly eighteenth century tactics because generals hadn't developed new strategies. In fact eighteenth century strategies, such as the mass bayonet charge, continued to be used into World War I despite the fact that military technology had made such strategies obsolete. To criticize McClellan for failing to adapt to the new battlefield produced by industrial war fails to ignore a larger problem in military thinking.

My second main issue is that Carhart criticizes McClellan for adopting less aggressive strategies to help minimize casualties, while at the same time lauding General Winfield Scott's Anaconda Plan. For those of you unfamiliar with American Civil War history, the Anaconda Plan involved a blockade of Southern ports by the US Navy and military control of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers by the US Army. This blockade would cut the mainly cotton growing Deep South from the food-producing regions of the Midwest as well as keep the South from selling its cotton to European textile mills. Like an anaconda squeezing its prey to death, Scott's plan would gradually squeeze the South to starvation and force their surrender. Scott predicted that this plan could be carried out by a relatively small number of men at very low cost in term of human lives and other resources. What Scott is basically doing, albeit on a larger scale, is besieging the South and starving them into submission, which Carhart states in his book is an eighteenth century strategy. However, Scott's Anaconda Plan, although mocked by contemporaries, was critical for winning the war and is celebrated as an excellent example of military strategy, even by Carhart. It simply annoys me that while McClellan and Scott both utilized a similar school of military thinking and used tactics in an attempt to decrease their overall casualties, Scott is lauded for it while McClellan is lambasted.

The other main issue I had with Carhart's book was a tendency for him to incorporate overly descriptive purple prose into the book. To clarify further on this point, a friend asked me if Carhart was simply trying to make history more accessible to general readers rather than just academics. I explained that making history accessible is one thing, describing how the juice of peaches dripped down the cheeks and jowls of a Confederate officer in shiny rivulets is entirely another. These overly detailed and unnecessary descriptions took away from the overall historical quality of the book.

Finally, the last issue I have with this book is Carhart's decision to focus on the careers of six officers. This decision ultimately forced the book in two directions that made it not work as well as it could have. On the one hand the book is, by focusing on six officers, biographical in nature and to an extent the book follows the lives of the six officers. However, Carhart also follows the overall campaigns in and around Northern Virginia during the war and serves as a general history book. As a result I feel that the focus of the book swings too far between extremes and doesn't as a good of a job as it could have if it had focused on being either a biography or a general history instead of being both.

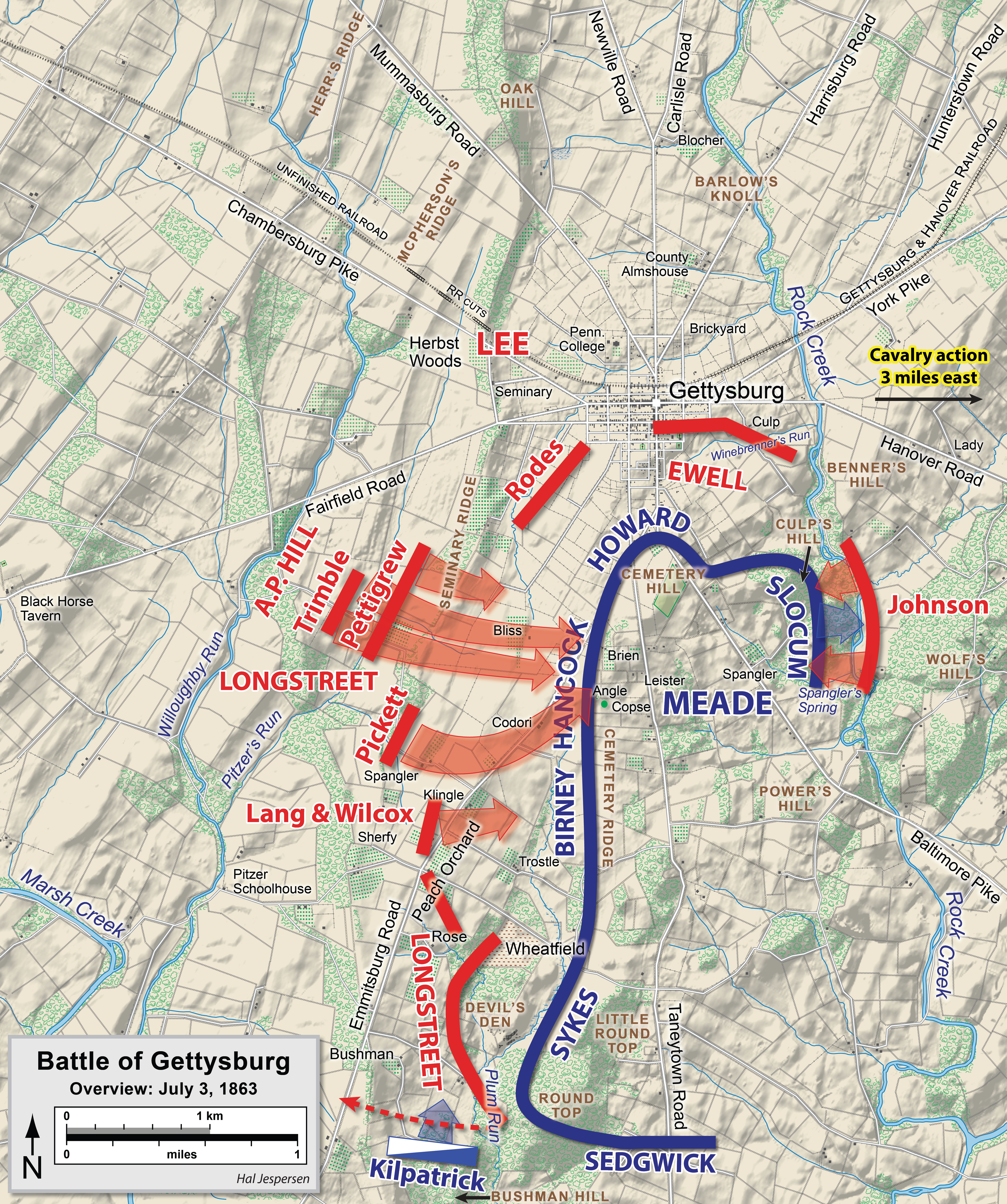

The one thing I liked about Sacred Ties was the chapter on Gettysburg, specifically his hypothesis about the third day of the battle. Let me clarify a little for people who are unfamiliar with the specifics of Gettysburg, which happened on July 1st-3rd in 1863. By July 3rd the Union Army had solidified defensive positions on the high ground to the south of Gettysburg. The union line was secured on Culp's and Cemetery Hill, takes a ninety degree turn to the south and ran along Cemetery Ridge before stopping at Big and Little Round Top hills to the south.

What has perplexed many historians is Lee's decision to send Pickett's division against the Union center, entrenched on Cemetery Ridge, in what proved to be a suicidal attack. Carhart provides perhaps the best hypothesis I have heard. He explains that General J.E.B. Stuart, leading the Confederate cavalry, attempted to flank the Union defenses and strike the Union rear in concert with Pickett's attack on the Union center as well as attacks from Ewell's corps on the Union right. This kind of strategy actually was fairly typical for Lee, who divided his army into multiple units that would strike the enemy in concerted attacks. What was key in Gettysburg, however, was Stuart's force of several thousand cavalry was stymied by George Custer and his units of Michigan Cavalry. Carhart hypothesizes that because Stuart's flanking maneuver was stopped by Custer and his cavalry they were unable to provide the necessary support for Pickett's attack at the Union center. I think it's a very good hypothesis and definitely goes a long way towards explaining the otherwise disastrous attack of Pickett's division on July 3rd.

Ultimately I have to say you're better off just passing this book by. Other than the chapter on Gettysburg the book doesn't bring anything new to the field of Civil War history. As a biography of six men it's too short and nowhere near as exhaustive as it should be, and as an overall history of the Civil War it's too narrow in scope. I sadly can't recommend more books about the Civil War for you to read at this time but I'm sure there are plenty out there. If you're interested in the biographies I'd check to see if there are any about the officers before going with this one.

- Kalpar

No comments:

Post a Comment