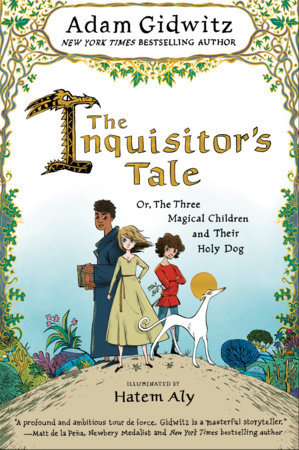

Today I'm looking at a book which was foisted upon me by one of my friends, The Inquisitor's Tale ,Or, The Three Magic Children and Their Holy Dog. This book is set in France in 1242 and was described to me as a modern-day reimagining of Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales and also done for children. And I have to admit, at least in the beginning the parallels with The Canterbury Tales is very pronounced, although I feel like it sort of tapers off as the book goes on.The main message of the book is also fairly heavy-handed but it's a good message so I can't fault Gidwitz too much.

The book begins with travellers in an inn, discussing the three magical children and their holy dog who have been declared outlaws by King Louis IX of France. But nobody precisely knows what the children have done to raise the ire of the king or who they are. However, the travellers in the inn start sharing stories, revealing that all of them know a little bit about the tale and together they're able to create a more coherent picture.

Gradually we are introduced to our four protagonists. First we have Gwenforte the greyhound, who died protecting baby Jeanne from an adder and was venerated as a saint by peasants in a village until Gwenforte was resurrected. And then there's Jeanne, the French peasant girl Gwenforte saved who can see the future. Next we meet William, an enormous oblate in a monastery whose father was a knight in the reconquista and whose mother was a Moor. William possesses enormous strength, capable of shattering a stone bench with his bare hands. Finally there's Jacob, a Jewish boy whose home village is burned down by some foolish Christian boys on a dare and who possesses the ability to miraculously heal any wound with different plants. The children eventually meet up and become boon companions.

Another way that this book is a lot like Canterbury Tales is there's a lot of low-brow humor, especially in the first third or so of the book. There's a point where peasants send a bunch of knights swimming through a dung heap looking for a child that isn't there, there's a farting dragon, and there's a pun on the multiple uses of the word ass. Considering that in The Miller's Tale, which is one of the ones I was forced to read in high school, two young students plan to bed another man's wife, one of them succeeds in doing so, the woman gets another one of the students to kiss her butt, and then the first student farts in the other student's face, the things I just described would totally not go amiss in one of the more comedic of Chaucer's tales. I do feel in hindsight that the humor doesn't fit as well because of the tonal shift around a third of the way through the book, but that's just me.

The main theme of the book is about tolerance in general and religious tolerance in specific. Now this is a theme which I'm all in favor of. I'm on board with loving your neighbor as yourself, even if it's really darn hard sometimes. But I feel like this book does it in kind of a heavy-handed way that it becomes too much. Obviously there are people who aren't into the whole tolerance thing in the first place, but I'm not sure they'd pick up this book in the first place and even if they did if it would change their minds at all. Maybe there are a few people who would benefit, but it feels a lot like Gidwitz is stating something his audience already agrees on with him.

Overall though, I thought this book was pretty good, in spite of the heavy-handedness and sharp tonal shift. The illuminations by Hatem Aly done within the book are wonderful to look at and occasionally capture the feeling of a true medieval manuscript. Gidwitz has also done significant research to ensure his book doesn't stray too far from the truth of medieval life in thirteenth century France. For anybody who enjoys all things medieval, I think this is worth a look.

- Kalpar

No comments:

Post a Comment