Today I'm looking at a semi-biography of Joan of Arc. I say this is a semi-biography because since Joan was really only in the public eye for a few years before she was executed for heresy, it's really hard to give more than a brief summary of her life. Otherwise the lives of ordinary peasant girls in late medieval France are largely unrecorded and we can only make best guesses. Of course, the life of Joan grows far more complicated because of the hundreds of years of mythology and symbolism that have grown up around her and in some ways taken away her humanity by putting her on a level above ordinary human beings.

Castor acknowledges this problem and so the book is not so much a biography of Joan as much as it's an attempt to put Joan into context. As she explicitly states, we do not follow Joan from her life in rural France and her journey to Chinon. Instead, we follow the movers and shakers of French politics for many years and are with Charles VII when Joan arrives at Chinon. And after Joan's trial and execution, we see not only the final stages of the Hundred Years War, but the afterlife Joan has enjoyed into the modern era.

Castor does an excellent job of setting the scene of fifteenth century France, torn between three factions. The French themselves were split into two factions, attempting to control the mentally ill Charles VI and, by extension, power at court. On the one hand were the Armagnac faction, eventually led by Prince Charles the dauphin of France who would become Charles VII, and on the other hand the Burgundian faction led by first John the Fearless and then his son Phillip, both Dukes of the increasingly autonomous region of Burgundy. Burgundy sat on the border between France and the Holy Roman Empire and owned land technically within both countries. On top of this the Dukes of Burgundy had extensive territories and interests in the Low Countries which tied them economically with the wool trade of the English. So what was good for Burgundy wasn't always what was good for France and created increased tension and outright violence between the dukes and their monarchs.

Exploiting this factionalism among the French, the English monarchs pressed their own competing claims for the French throne and managed to make extensive gains in Normandy while the French fought amongst themselves. Victories such as Agincourt, where outnumbered English archers and infantry absolutely massacred armies of French knights, created an aura of invincibility around the English army and their warrior-king Henry V. Even with Henry's death by a fever, the French had a strong fear of going against the apparently unconquerable English and when the city of Orleans was besieged by the English, it seemed only a matter of time before they would gain this crucial crossing of the Loire and advance into the strongholds of the Armagnac faction.

When Joan arrived at Chinon, declaring she had been sent by God to ensure Charles would be crowned and anointed King of France with the holy Oil of Clovis, it caused a good deal of consternation. Some people believed her, some people didn't, but almost nobody was sure what to do with her. After considerable debate among theologians it was concluded that if Joan was truly sent by God to save France, then she would accomplish a sign. As the city of Orleans needed to be relieved from its besiegers and an army would have been sent there anyway, this was deemed an appropriate task for Joan to accomplish. If she failed, well no harm done and at least they tried to save Orleans. But if she succeeded, then perhaps God had finally come to save the most Christian kingdom on earth.

As Castor depicts it, and as I've read in some other sources, the biggest asset Joan had was as a morale booster for the highly discouraged French forces. French armies that should have been victorious on the field of battle had been utterly routed by numerically inferior English forces. An army that goes into battle expecting to lose will almost certainly find a way to lose regardless of any advantages. But with Joan, who claimed to have been sent by God to redeem France and expel the hated English, the French armies were able to believe they actually stood a chance at victory. Once Joan was victorious not only at Orleans, but at other battles as well, it is small surprise that the French began to believe they were now invincible and the English feared to face against any army headed by Joan. It is small surprise that the English and their allies were incredibly pleased when Joan was captured and engaged in an extensive heresy trial to remove Joan from the equation entirely.

What is remarkable about Joan, aside from her ability to win against the English, is the very fact that she is remembered today. Fifteenth century France certainly wasn't short on mystics, holy seers, or other individuals who claimed a mission from God. Joan enjoyed some brief success, but she suffered some failures as well and was condemned by the Catholic Church as a heretic and burned at the stake. It seems almost odd that Joan has remained not only in the popular consciousness but became as saint of the Roman Catholic Church as well. Perhaps it was because Joan's trial for heresy, and then twenty-five years later the trial overturning that decision of heresy, were such big news in their eras that Joan's legacy has endured. Certainly Jan Huss, whose followers had as great an effect in Bohemia as Joan had in France, is less well known among Americans. Perhaps it was ultimately just one of those accidents of history which we may never truly understand. But five hundred years later it is still difficult to sort out Joan the person from Joan the saint.

- Kalpar

Tuesday, May 30, 2017

Thursday, May 25, 2017

The Falcon Throne, by Karen Miller

Today I'm looking at the first in a newer fantasy series, The Falcon Throne, which deals with two duchies, Clemen and

Harcia, which were once united under one kingdom but have been split for about two hundred years. The book jumps through about twenty years of events within both duchies, as well as some events further abroad, and we are shown that there are larger powers at work than just the nobles contesting for the Falcon Throne and leaves the future of the duchies, as well as the wider world, in considerable doubt.

The book splits its focus between three main groups of characters. In the north we have the ruling family of the duchy of Harcia, Duke Aimery, along with his sons Balfre and Grefin. Balfre is Aimery's oldest surviving son but extremely violent and ill-tempered and harbors dreams of reuniting the two duchies under one crown at swordpoint. This dismays his father and younger brother, who desire peace between the two duchies and accept that the split appears permanent.

To the south is Duke Harald of Clemen, a despicable tyrant who has driven a group of his nobles to hatch a plan to depose him and replace him with his bastard-born cousin, Ederic. Harald gets bumped off pretty early in the book so most of the action in Clemen is Ederic trying to repair the damage Harald has done and struggling as Clemen suffers catastrophe after catastrophe under his reign.

Finally there is Liam in the Marches, the border region between the two duchies. Liam is Harald's natural born son, rescued by his nurse from the castle the night his parents are killed and raised in obscurity at an inn in the center of the Marches. Only Liam and his nurse know his true identity, but Liam is no less determined to regain his throne. There are some other plots as well but they don't get nearly as much attention as these other three.

The biggest thing I felt about this book was it was trying very hard to be like Game of Thrones, but it fell far short of the quality that makes people love the heck out of that series. One of the things was I never felt very emotionally invested in any of the characters. Martin has a way of making characters seem three dimensional and provoking an emotional reaction from the reader. Miller's characters just feel flat by comparison. A good example is comparing Balfre versus Joffrey. They're both pretty nasty pieces of work that you would never, ever want in a position of authority but thanks to monarchy thousands of people will be ruled by these terrible individuals. But Joffrey provokes far more of an emotional reaction out of me than Balfre does. It's not a positive reaction, but I don't think there's anybody familiar with Game of Thrones that doesn't love to hate Joffrey. And that makes him a much better character because he provokes an emotional response from the audience.

Balfre, by comparison, is just kind of annoying.I dislike him, but it never goes beyond a mild, ''Oh great, another power-hungry maniac that's determined to make himself king'' dislike. Joffrey I wanted to punch in the face so, so many times and I was actually happy when he [SPOILERS SPOILER SPOILERS]. But Balfre I just wanted to go away and stop bothering me with his evil moustache-twirling.

This becomes even weaker when it comes to characters we're supposed to like. There's such a plethora of well-written characters in Game of Thrones that everyone has their own favorite. Whether it's Jon Snow, Arya Stark, Daenerys Targaryen, or my personal favorite, Davos Seaworth, you have characters that are interesting and you actually care about. Which is why people get so upset when Martin kills people off, we actually cares what happens to them. And a number of people do get killed off in this book, but when it happened I found myself just...not caring. Which I don't think is a good sign for your book if your reader isn't emotionally invested in your characters.

Another way I felt this book was trying to be like Game of Thrones was by being ''edgy'' compared to some of the more ''traditional'' fantasy. Aside from the sheer number of great characters, Game of Thrones is also famous for its ridiculous amount of gratuitous sex and violence, which even in Game of Thrones can get a little excessive. But the biggest way The Falcon Throne seemed to do this was by having the word fuck be used a lot. It just feels like a very unsophisticated way to make the book seem edgier.

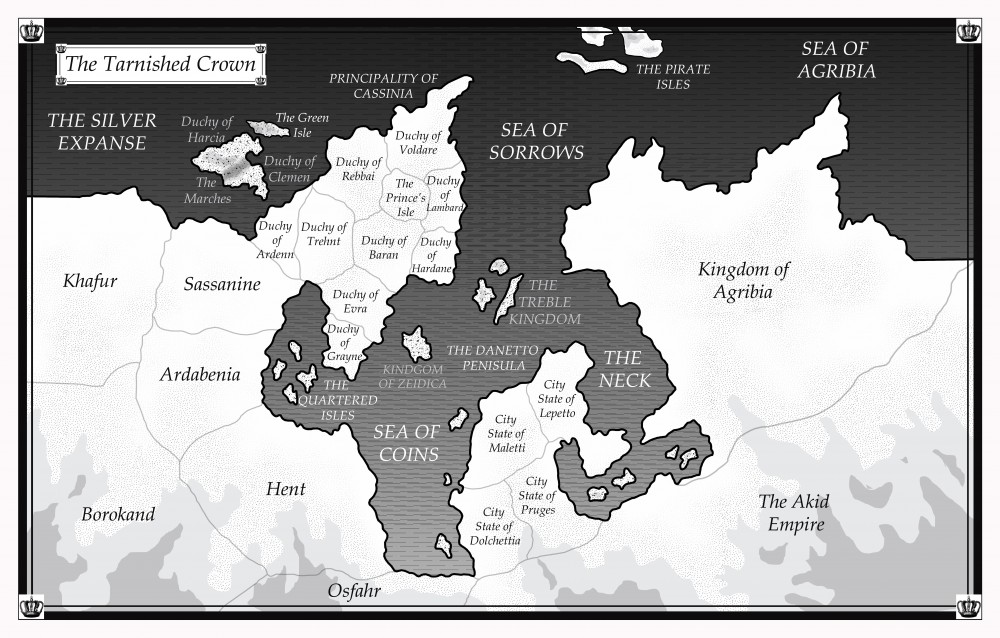

Although I think the biggest problem this book had was scale. Let me get a map just for sake of comparison here.

Okay, you see those two itty bitty islands up in the top left corner of the map? That's where around 97% of the action in this book takes place. There's some stuff that happens outside the island, but for the most part it's all up in those two little islands. Now, you've all probably seen this before, but let's pull up Westeros.

So here we've got stuff going on all over that big landmass to the left of the map, and then there's stuff going on in other parts of the map as well. We're talking about events that are continent-spanning in their scope and threaten to change the fate of the entire world. But with The Falcon Throne? We're basically looking at a border dispute between two neighbors on a tiny island. It just doesn't have the same feel of epic magnitude that Game of Thrones which makes it feel just not as important a conflict. And by jumping through events over a twenty year period, while important in helping Liam get old enough to be able to contest his throne, it also makes it seem like there wasn't enough material to make the book as long as it was and it makes me wonder what the later books in this series would talk about.

Ultimately this book doesn't really have anything to recommend it. There's a larger, darker plot going on but for the most part it seems like a dispute over who gets to be in charge of a tiny little island in a much larger world. And because none of the characters spark my interest, I find myself not caring who ends up sitting in the fancy chair. Considering how darn long this book is and how much of a disappointment it was, I would definitely recommend staying away from it.

- Kalpar

Harcia, which were once united under one kingdom but have been split for about two hundred years. The book jumps through about twenty years of events within both duchies, as well as some events further abroad, and we are shown that there are larger powers at work than just the nobles contesting for the Falcon Throne and leaves the future of the duchies, as well as the wider world, in considerable doubt.

The book splits its focus between three main groups of characters. In the north we have the ruling family of the duchy of Harcia, Duke Aimery, along with his sons Balfre and Grefin. Balfre is Aimery's oldest surviving son but extremely violent and ill-tempered and harbors dreams of reuniting the two duchies under one crown at swordpoint. This dismays his father and younger brother, who desire peace between the two duchies and accept that the split appears permanent.

To the south is Duke Harald of Clemen, a despicable tyrant who has driven a group of his nobles to hatch a plan to depose him and replace him with his bastard-born cousin, Ederic. Harald gets bumped off pretty early in the book so most of the action in Clemen is Ederic trying to repair the damage Harald has done and struggling as Clemen suffers catastrophe after catastrophe under his reign.

Finally there is Liam in the Marches, the border region between the two duchies. Liam is Harald's natural born son, rescued by his nurse from the castle the night his parents are killed and raised in obscurity at an inn in the center of the Marches. Only Liam and his nurse know his true identity, but Liam is no less determined to regain his throne. There are some other plots as well but they don't get nearly as much attention as these other three.

The biggest thing I felt about this book was it was trying very hard to be like Game of Thrones, but it fell far short of the quality that makes people love the heck out of that series. One of the things was I never felt very emotionally invested in any of the characters. Martin has a way of making characters seem three dimensional and provoking an emotional reaction from the reader. Miller's characters just feel flat by comparison. A good example is comparing Balfre versus Joffrey. They're both pretty nasty pieces of work that you would never, ever want in a position of authority but thanks to monarchy thousands of people will be ruled by these terrible individuals. But Joffrey provokes far more of an emotional reaction out of me than Balfre does. It's not a positive reaction, but I don't think there's anybody familiar with Game of Thrones that doesn't love to hate Joffrey. And that makes him a much better character because he provokes an emotional response from the audience.

Balfre, by comparison, is just kind of annoying.I dislike him, but it never goes beyond a mild, ''Oh great, another power-hungry maniac that's determined to make himself king'' dislike. Joffrey I wanted to punch in the face so, so many times and I was actually happy when he [SPOILERS SPOILER SPOILERS]. But Balfre I just wanted to go away and stop bothering me with his evil moustache-twirling.

This becomes even weaker when it comes to characters we're supposed to like. There's such a plethora of well-written characters in Game of Thrones that everyone has their own favorite. Whether it's Jon Snow, Arya Stark, Daenerys Targaryen, or my personal favorite, Davos Seaworth, you have characters that are interesting and you actually care about. Which is why people get so upset when Martin kills people off, we actually cares what happens to them. And a number of people do get killed off in this book, but when it happened I found myself just...not caring. Which I don't think is a good sign for your book if your reader isn't emotionally invested in your characters.

Another way I felt this book was trying to be like Game of Thrones was by being ''edgy'' compared to some of the more ''traditional'' fantasy. Aside from the sheer number of great characters, Game of Thrones is also famous for its ridiculous amount of gratuitous sex and violence, which even in Game of Thrones can get a little excessive. But the biggest way The Falcon Throne seemed to do this was by having the word fuck be used a lot. It just feels like a very unsophisticated way to make the book seem edgier.

Although I think the biggest problem this book had was scale. Let me get a map just for sake of comparison here.

Okay, you see those two itty bitty islands up in the top left corner of the map? That's where around 97% of the action in this book takes place. There's some stuff that happens outside the island, but for the most part it's all up in those two little islands. Now, you've all probably seen this before, but let's pull up Westeros.

So here we've got stuff going on all over that big landmass to the left of the map, and then there's stuff going on in other parts of the map as well. We're talking about events that are continent-spanning in their scope and threaten to change the fate of the entire world. But with The Falcon Throne? We're basically looking at a border dispute between two neighbors on a tiny island. It just doesn't have the same feel of epic magnitude that Game of Thrones which makes it feel just not as important a conflict. And by jumping through events over a twenty year period, while important in helping Liam get old enough to be able to contest his throne, it also makes it seem like there wasn't enough material to make the book as long as it was and it makes me wonder what the later books in this series would talk about.

Ultimately this book doesn't really have anything to recommend it. There's a larger, darker plot going on but for the most part it seems like a dispute over who gets to be in charge of a tiny little island in a much larger world. And because none of the characters spark my interest, I find myself not caring who ends up sitting in the fancy chair. Considering how darn long this book is and how much of a disappointment it was, I would definitely recommend staying away from it.

- Kalpar

Tuesday, May 23, 2017

A Natural History of Dragons, by Marie Brennan

Today I'm looking at A Natural History of Dragons, which is the first book in a series that makes up the memoirs of Lady Trent, a famous dragon researcher within the book's universe. The books are set in what appears to be the equivalent of our nineteenth century. Early on steam engines and steam-powered transportation is rare but not unheard of, but it id implied by Lady Trent that such developments such as railroads and steamships become commonplace within the book's universe. It is also an era when great researches into biology and natural history are being undertaken. The most tantalizing, and perhaps most difficult, is the study of dragons.

Dragons are already fierce predators and live in some of the most inhospitable climates in the world. In addition to being large, winged predators, they have fearsome breath weapons which makes just approaching the beasts dangerous. The research of dragons is also hampered by the extreme rate at which dragon bones decay, usually within a matter of days of the death of the dragon, making the collection of specimens for protracted study almost impossible.

Although to be honest the dragons felt mostly like a side-show because most of the focus is on the main character, Isabella, Lady Trent. As I mentioned, this book is the first in a series written from Lady Trent's perspective as memoirs of her career. This book deals with roughly the first twenty years of her life which takes us to the end of her first field expedition, undertaken with her husband and two other researchers. We meet Isabella as a very curious girl who first begins on scientific inquiry by wondering why birds have wishbones, specifically the evolutionary purpose of a wishbone. This leads to her dissecting a dead dove she found in the garden and a lifelong investigation into science. Of course, this sort of scientific inquiry is not seen by her mother as an appropriate interest for young ladies, but her father is far more lenient on the matter and is willing to indulge Isabella to a degree. Eventually she meets Jacob, a gentleman also deeply interested in natural history, and they get married.

Eventually Isabella and Jacob join an expedition to research rock wyrms, a species of dragon. The result is interesting, although I was left with the feeling of it being far more mundane than I hoped. And I'm not sure if that's a good thing or a bad thing. On the one hand, you'd expect dragons and creatures like them such as drakes a wyverns to be exceptional creatures, mostly because we don't have any of them in the real world. On the other hand, the mundanity that Isabella approaches the topic at times seems downright appropriate. Because these books are vaguely steampunkish it makes sense for dragons to be just another species for scientists to observe, dissect, and categorize as they expand the limits of man's biological knowledge. So it's kind of weird to see dragons depicted as just another species to be studied, rather than magical creatures. But I think it's a good kind of different.

Overall I think this book is definitely a starter book for the series because it introduces Isabella and gets her started on her path of scientific research. I'm hoping that later books will expand on her career more and we'll get to see more dragons, especially Isabella interacting with them, than we have in this one.

- Kalpar

Dragons are already fierce predators and live in some of the most inhospitable climates in the world. In addition to being large, winged predators, they have fearsome breath weapons which makes just approaching the beasts dangerous. The research of dragons is also hampered by the extreme rate at which dragon bones decay, usually within a matter of days of the death of the dragon, making the collection of specimens for protracted study almost impossible.

Although to be honest the dragons felt mostly like a side-show because most of the focus is on the main character, Isabella, Lady Trent. As I mentioned, this book is the first in a series written from Lady Trent's perspective as memoirs of her career. This book deals with roughly the first twenty years of her life which takes us to the end of her first field expedition, undertaken with her husband and two other researchers. We meet Isabella as a very curious girl who first begins on scientific inquiry by wondering why birds have wishbones, specifically the evolutionary purpose of a wishbone. This leads to her dissecting a dead dove she found in the garden and a lifelong investigation into science. Of course, this sort of scientific inquiry is not seen by her mother as an appropriate interest for young ladies, but her father is far more lenient on the matter and is willing to indulge Isabella to a degree. Eventually she meets Jacob, a gentleman also deeply interested in natural history, and they get married.

Eventually Isabella and Jacob join an expedition to research rock wyrms, a species of dragon. The result is interesting, although I was left with the feeling of it being far more mundane than I hoped. And I'm not sure if that's a good thing or a bad thing. On the one hand, you'd expect dragons and creatures like them such as drakes a wyverns to be exceptional creatures, mostly because we don't have any of them in the real world. On the other hand, the mundanity that Isabella approaches the topic at times seems downright appropriate. Because these books are vaguely steampunkish it makes sense for dragons to be just another species for scientists to observe, dissect, and categorize as they expand the limits of man's biological knowledge. So it's kind of weird to see dragons depicted as just another species to be studied, rather than magical creatures. But I think it's a good kind of different.

Overall I think this book is definitely a starter book for the series because it introduces Isabella and gets her started on her path of scientific research. I'm hoping that later books will expand on her career more and we'll get to see more dragons, especially Isabella interacting with them, than we have in this one.

- Kalpar

Thursday, May 18, 2017

The Fear Institute, by Jonathan L. Howard

Today I'm looking at the third book in the Johannes Cabal series, The Fear Institute. I know I've said in the past that I'm not sure quite what to think about this series because Johannes is such a questionable character but there's a certain wittiness about these books that makes them enjoyable to listen to as well. This book, however, is definitely different from the others. Not necessarily bad because it's got its own merits, but definitely different in tone and subject material.

In this book Johannes is approached by three gentlemen from the Fear Institute, an organization that seeks to eliminate irrational human fear forever. To do this they seek to employ Cabal as a guide in investigating the Dreamlands, a realm on the other side of sleep populated by both dreams and nightmares. Because access to the Dreamlands would be extremely beneficial for his ongoing researches, Cabal agrees to guide the gentlemen and then becomes involved in a rather odd adventure.

The plot of this book owes pretty much everything to Lovecraft. The Dreamlands are one of Lovecraft's multiple inventions and Cabal and the men from the Fear Institute head to Arkham, Massachusetts to enter the Dreamlands. Along the way they are pursued by Lovecraftian ghouls and references are made to C'thulu and Azathoth. Most importantly, Cabal calls upon the power of Nyarlathotep in a dicy situation and soon discovers he may have actually gotten the attention of the mad deity, which is never a good thing.

And I think that's really the problem for me with the book, I'm just not a big Lovecraft fan. I've read most of Lovecraft's original works and a small selection of Lovecraft-inspired stories and it's just...not for me. Obviously there's a big fandom that eats his stuff up but for whatever reason I just don't get the appeal. I think part of it is the whole, ''We're less than insignificant specks of dust on a cosmic scale'' thing. Which for me is, ''Whew, that's a whole lot off of my mind.'' And when it comes to elder gods beyond my comprehension I just...I can't spare the brain space to worry about them apparently. So since this is very much a Lovecraft story but with Cabal as the main character, I feel like I'm at a bit of a disadvantage with this book.

I also feel like some of the bitingly dry humor that was in the previous books and made me enjoy them was kind of lacking in this one. It may have just been a function of this basically being a Lovecraft story where humor doesn't work as well, but I'm not entirely sure. So ultimately I don't think this book is bad, just different and not exactly my area of interests.

If you like Lovecraft and you enjoyed the earlier Cabal books, you'd definitely like this one. But if Lovecraft isn't quite your cup of tea then this might just be an okay read at best.

- Kalpar

In this book Johannes is approached by three gentlemen from the Fear Institute, an organization that seeks to eliminate irrational human fear forever. To do this they seek to employ Cabal as a guide in investigating the Dreamlands, a realm on the other side of sleep populated by both dreams and nightmares. Because access to the Dreamlands would be extremely beneficial for his ongoing researches, Cabal agrees to guide the gentlemen and then becomes involved in a rather odd adventure.

The plot of this book owes pretty much everything to Lovecraft. The Dreamlands are one of Lovecraft's multiple inventions and Cabal and the men from the Fear Institute head to Arkham, Massachusetts to enter the Dreamlands. Along the way they are pursued by Lovecraftian ghouls and references are made to C'thulu and Azathoth. Most importantly, Cabal calls upon the power of Nyarlathotep in a dicy situation and soon discovers he may have actually gotten the attention of the mad deity, which is never a good thing.

And I think that's really the problem for me with the book, I'm just not a big Lovecraft fan. I've read most of Lovecraft's original works and a small selection of Lovecraft-inspired stories and it's just...not for me. Obviously there's a big fandom that eats his stuff up but for whatever reason I just don't get the appeal. I think part of it is the whole, ''We're less than insignificant specks of dust on a cosmic scale'' thing. Which for me is, ''Whew, that's a whole lot off of my mind.'' And when it comes to elder gods beyond my comprehension I just...I can't spare the brain space to worry about them apparently. So since this is very much a Lovecraft story but with Cabal as the main character, I feel like I'm at a bit of a disadvantage with this book.

I also feel like some of the bitingly dry humor that was in the previous books and made me enjoy them was kind of lacking in this one. It may have just been a function of this basically being a Lovecraft story where humor doesn't work as well, but I'm not entirely sure. So ultimately I don't think this book is bad, just different and not exactly my area of interests.

If you like Lovecraft and you enjoyed the earlier Cabal books, you'd definitely like this one. But if Lovecraft isn't quite your cup of tea then this might just be an okay read at best.

- Kalpar

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Jhereg, by Steven Brust

Today I'm looking at a book which was loaned to me by a friend, Jhereg. Doing a little digging around I found out that this is actually the fourth book chronologically in the series, but the first one which was published. And I can definitely say that this book feels a little incomplete. It's pretty short and I can see a lot of areas where it could have been expanded but otherwise it's pretty good.

Jhereg follows the life of Vlad Taltos, who is apparently talked about more in other books but this is the first time we meet him and his jhereg familiar, Loiosh. Vlad is an Easterner or human, at least what passes for human in this series. A good chunk of the world is ruled by the Dragaeran Empire, the Dragaerans being a tall, long-lived species with an affinity for sorcery and other abilities. So...kind of elves and yet kind of not at the same time? It's a little confusing. As a result Easterners, aka humans, have second-class citizen status within the Empire. Anyway, the Dragaeran are divided into seventeen different houses with different specialties. The Dragons, for example, are great warriors and generals, while the Jhereg are spies, thieves, and assassins. Vlad's father actually purchased a title within the Jhereg House, making Vlad have something approaching equal rights with the Dragaerans but still the taint of being an Easterner by blood.

The plot centers around an assassination mission that Vlad has been hired for by one of the members of the Jhereg council, known only as ''The Demon''. Apparently an individual named Mellar has absconded with over nine million gold imperials of the council's operating funds. Aside from seriously hampering council operations, if word of Mellar's theft leaks out and he remains unpunished then the respect and fear that most of the criminal underworld has for the Jhereg council will disappear overnight, permanently weakening the house's power. Vlad has to find Mellar soon and take him out, the only trouble being nobody knows exactly where he's gone.

The plot is pretty good and Brust does a really excellent job of world-building in his book. I could have used a little more exposition, but it does manage to avoid that ''as you should already know'' lectures of exposition that some sci-fi and fantasy series fall prey to very easily. I can see that Brust has developed a very complex world in his mind and I kind of wish we'd gotten to explore it more in a longer book, rather than the 240 page book that we ended up getting. But there is the possibility that the world gets explored more in-depth in later books.

There are also a couple of plotlines that get introduced but are really incidental to the ''we need to kill Mellar so everyone takes Jheregs seriously'' plotline, to the point I almost feel like Brust was cramming too much stuff in. As I said it's a pretty short book so I almost wonder if we might have gotten more about the assassination plot if he wasn't throwing in all these big side plots which make the world feel a lot more complex, although sometimes feeling a little too complex.

Overall this was a short and pretty interesting read. This definitely felt like Brust had enough ideas to make this a huge, door-stopper tome like some of Martin's books or other fantasy books that I've read. But its brevity makes it a good weekend read. If anything, I wish it had been at least a little longer for some more development and in-depth exploration.

- Kalpar

Jhereg follows the life of Vlad Taltos, who is apparently talked about more in other books but this is the first time we meet him and his jhereg familiar, Loiosh. Vlad is an Easterner or human, at least what passes for human in this series. A good chunk of the world is ruled by the Dragaeran Empire, the Dragaerans being a tall, long-lived species with an affinity for sorcery and other abilities. So...kind of elves and yet kind of not at the same time? It's a little confusing. As a result Easterners, aka humans, have second-class citizen status within the Empire. Anyway, the Dragaeran are divided into seventeen different houses with different specialties. The Dragons, for example, are great warriors and generals, while the Jhereg are spies, thieves, and assassins. Vlad's father actually purchased a title within the Jhereg House, making Vlad have something approaching equal rights with the Dragaerans but still the taint of being an Easterner by blood.

The plot centers around an assassination mission that Vlad has been hired for by one of the members of the Jhereg council, known only as ''The Demon''. Apparently an individual named Mellar has absconded with over nine million gold imperials of the council's operating funds. Aside from seriously hampering council operations, if word of Mellar's theft leaks out and he remains unpunished then the respect and fear that most of the criminal underworld has for the Jhereg council will disappear overnight, permanently weakening the house's power. Vlad has to find Mellar soon and take him out, the only trouble being nobody knows exactly where he's gone.

The plot is pretty good and Brust does a really excellent job of world-building in his book. I could have used a little more exposition, but it does manage to avoid that ''as you should already know'' lectures of exposition that some sci-fi and fantasy series fall prey to very easily. I can see that Brust has developed a very complex world in his mind and I kind of wish we'd gotten to explore it more in a longer book, rather than the 240 page book that we ended up getting. But there is the possibility that the world gets explored more in-depth in later books.

There are also a couple of plotlines that get introduced but are really incidental to the ''we need to kill Mellar so everyone takes Jheregs seriously'' plotline, to the point I almost feel like Brust was cramming too much stuff in. As I said it's a pretty short book so I almost wonder if we might have gotten more about the assassination plot if he wasn't throwing in all these big side plots which make the world feel a lot more complex, although sometimes feeling a little too complex.

Overall this was a short and pretty interesting read. This definitely felt like Brust had enough ideas to make this a huge, door-stopper tome like some of Martin's books or other fantasy books that I've read. But its brevity makes it a good weekend read. If anything, I wish it had been at least a little longer for some more development and in-depth exploration.

- Kalpar

Thursday, May 11, 2017

Dark Money, by Jane Mayer

Today I'm looking at something that again might be a little controversial, Dark Money by Jane Mayer. This book tracks the rise of the reactionary right and their support by the billionaire donor class, with the infamous Koch brothers as some of the greatest players and organizers behind this largely hidden political machine. As for the accuracy of this book, I have two main concerns. The first is since the activities that Mayer is reporting on are, as she describes them, largely hidden from the public eye behind a veil of front organizations and anonymity. Piercing this veil and following the money trail can be incredibly difficult and even Mayer admits that not all the information can be dug up so the puzzle that we have is incomplete. The second issue is, since I listened to this as an audio book I do not know how thoroughly Mayer's researched this topic and what her sources are. Granted even if I had read this book I don't know if seeing the citations would help me that much one way or the other. I will say that the amount of research presented within the body of the book is at least impressive enough to make me think Mayer is raising some legitimate points.

In this book Mayer records how over the past half-century, from the John Birch Society in the 1960's to today's Tea Party movement, the Koch brothers and other wealthy donors have been involved in moving libertarian ideology from the fringe of American politics closer to its center. And from at least an objective standpoint there has been a strong shift rightward on economic policy among the Republican, and to an extent also the Democratic parties, especially after the Reagan years of the 1980s. But what Mayer describes is a decades-long conspiracy by the Kochs and other libertarians, to manufacture public support for their ideology through organizations such as think tanks, social welfare groups, charities, political action committees, and the establishment of libertarian-leaning programs in prominent universities. As Mayer depicts it, the Kochs have been involved in creating safe spaces for libertarian ideology for years and it is finally reaping dividends with the Tea Party movement and the shift right of the Republican party.

And I have to admit, there is compelling evidence within my own experience to support Mayer's assertions. I have several relatives who have bought into the ideology spread by Fox News and other conservative outlets for years. Mainstream institutions such as the media, universities, and the government itself are depicted as bastions of ''liberal ideology'', bent on crushing hard-working (white) Americans by taxing and regulating them to death in some socialist nightmare. I've seen first hand how exposure to the echo chamber can make people convinced they're the most oppressed people in the country. But to suggest as Mayer does that this has been a concentrated campaign lasting decades, orchestrated by a clique of super-wealthy libertarians, does stretch the boundaries of credulity.

And yet at the same time we can see the evidence. Ideologies that would have been unthinkable in previous decades, such as the gutting of the EPA, the repeal of minimum wage and child labor laws, and the abolition of institutions such as Social Security and Medicare, have been bandied about in all seriousness. Surely these ideas, which wouldn't have been considered by even the most conservative Republican or Dixiecrat fifty years ago, had to come from somewhere? And so the evidence does point to organizations funded at least in part by the Kochs and their allies.

If the material covered in this book is even halfway true, it paints a very grim picture for the American future. I am actually writing this review on the eve before Election Day so regardless how tomorrow turns out I'm left with the feeling the increased divisiveness in American politics will remain. If, as Mayer asserts, the Republican party has become beholden to the reactionary millionaire and billionaire donor base, then there is little reason for them to compromise and all the incentive in the world to continue pushing to the right, trying to undo a century of progress and reform in the United States. I can only hope things look better six months later when this finally posts.

- Kalpar

In this book Mayer records how over the past half-century, from the John Birch Society in the 1960's to today's Tea Party movement, the Koch brothers and other wealthy donors have been involved in moving libertarian ideology from the fringe of American politics closer to its center. And from at least an objective standpoint there has been a strong shift rightward on economic policy among the Republican, and to an extent also the Democratic parties, especially after the Reagan years of the 1980s. But what Mayer describes is a decades-long conspiracy by the Kochs and other libertarians, to manufacture public support for their ideology through organizations such as think tanks, social welfare groups, charities, political action committees, and the establishment of libertarian-leaning programs in prominent universities. As Mayer depicts it, the Kochs have been involved in creating safe spaces for libertarian ideology for years and it is finally reaping dividends with the Tea Party movement and the shift right of the Republican party.

And I have to admit, there is compelling evidence within my own experience to support Mayer's assertions. I have several relatives who have bought into the ideology spread by Fox News and other conservative outlets for years. Mainstream institutions such as the media, universities, and the government itself are depicted as bastions of ''liberal ideology'', bent on crushing hard-working (white) Americans by taxing and regulating them to death in some socialist nightmare. I've seen first hand how exposure to the echo chamber can make people convinced they're the most oppressed people in the country. But to suggest as Mayer does that this has been a concentrated campaign lasting decades, orchestrated by a clique of super-wealthy libertarians, does stretch the boundaries of credulity.

And yet at the same time we can see the evidence. Ideologies that would have been unthinkable in previous decades, such as the gutting of the EPA, the repeal of minimum wage and child labor laws, and the abolition of institutions such as Social Security and Medicare, have been bandied about in all seriousness. Surely these ideas, which wouldn't have been considered by even the most conservative Republican or Dixiecrat fifty years ago, had to come from somewhere? And so the evidence does point to organizations funded at least in part by the Kochs and their allies.

If the material covered in this book is even halfway true, it paints a very grim picture for the American future. I am actually writing this review on the eve before Election Day so regardless how tomorrow turns out I'm left with the feeling the increased divisiveness in American politics will remain. If, as Mayer asserts, the Republican party has become beholden to the reactionary millionaire and billionaire donor base, then there is little reason for them to compromise and all the incentive in the world to continue pushing to the right, trying to undo a century of progress and reform in the United States. I can only hope things look better six months later when this finally posts.

- Kalpar

Tuesday, May 9, 2017

Pebble in the Sky, by Isaac Asimov

Today I'm looking at Pebble in the Sky, by Isaac Asimov, which was his first full-length novel. While works like the Foundation short stories or the robot stories of I, Robot would later be collected in novel form, this was the first book written by Asimov as a full-length novel. That being said, it feels kind of rough around the edges which is a little odd considering I've known Asimov to write good short stories and to write good full-length novels so it may have been just an awkward transition between the mediums for him.

Pebble in the Sky, is actually the third book, chronologically, of the Empire series, set between the Robot stories and the Foundation stories of Asimov's greater literary universe. After doing some digging around I found that the Empire books, opposed to the Foundation or the Robot books, are separated by centuries and while they deal with the rise of the Trantor-dominated Galactic Empire, the three books don't necessarily connect one to the other. I may take a look at The Stars Like Dust and The Currents of Space because they sound like things I might be interested in reading and/or listening to. But I feel like this book is muddled more than anything else.

The biggest problem, I think, is that there are a lot of different plotlines going on at once and since the book isn't all that long in the first place, it feels like none of them get as well developed as they might have been. We begin with Joseph Schwartz, a retired tailor living in Chicago in 1949, out for a morning walk. Suddenly a mysterious atomic energy experiment attacks and flings Schwartz into the distant future where Earth is just one of hundreds of thousands of worlds in the Galactic Empire. Instead of being the capital of this mighty empire, or even revered as the cradle of humanity, Earth is reviled as a provincial backwater, the only inhabited planet polluted with high levels of radiation. Because resources on Earth are so scarce, the population is strictly controlled and once a person reaches sixty years of age they are euthanized, an issue of special concern for Schwartz since he is sixty-two.

If that had been the only plot in the book, a temporal fish-out-of-water situation, I think it might have been better than ''just okay''. Unfortunately Asimov starts cramming in a bunch of other plotlines and while they all end up tying together, it feels very disjointed. We have scientists working on a device that increases the synaptic connections in human beings, making them more intelligent. We have an archaeologist who thinks Earth may be the original home of humanity, opposed to the more commonly held belief that humanity evolved on separate worlds and was able to interbreed with the advent of interstellar flight. And we have a shadowy cloak and dagger conspiracy among the ministers of Earth's home government which ends up taking over the book. I think if Asimov had stuck with one or maybe two of these plots it would have been a lot better, but with four it kind of turns into a jumbled mess.

The only other complaint I could think to make is the book feels very much like it was written in the 1950's with the mores of the time period, but there's not really a lot we can do about that. It's okay, I just think it could have used a bit tighter focus.

- Kalpar

Pebble in the Sky, is actually the third book, chronologically, of the Empire series, set between the Robot stories and the Foundation stories of Asimov's greater literary universe. After doing some digging around I found that the Empire books, opposed to the Foundation or the Robot books, are separated by centuries and while they deal with the rise of the Trantor-dominated Galactic Empire, the three books don't necessarily connect one to the other. I may take a look at The Stars Like Dust and The Currents of Space because they sound like things I might be interested in reading and/or listening to. But I feel like this book is muddled more than anything else.

The biggest problem, I think, is that there are a lot of different plotlines going on at once and since the book isn't all that long in the first place, it feels like none of them get as well developed as they might have been. We begin with Joseph Schwartz, a retired tailor living in Chicago in 1949, out for a morning walk. Suddenly a mysterious atomic energy experiment attacks and flings Schwartz into the distant future where Earth is just one of hundreds of thousands of worlds in the Galactic Empire. Instead of being the capital of this mighty empire, or even revered as the cradle of humanity, Earth is reviled as a provincial backwater, the only inhabited planet polluted with high levels of radiation. Because resources on Earth are so scarce, the population is strictly controlled and once a person reaches sixty years of age they are euthanized, an issue of special concern for Schwartz since he is sixty-two.

If that had been the only plot in the book, a temporal fish-out-of-water situation, I think it might have been better than ''just okay''. Unfortunately Asimov starts cramming in a bunch of other plotlines and while they all end up tying together, it feels very disjointed. We have scientists working on a device that increases the synaptic connections in human beings, making them more intelligent. We have an archaeologist who thinks Earth may be the original home of humanity, opposed to the more commonly held belief that humanity evolved on separate worlds and was able to interbreed with the advent of interstellar flight. And we have a shadowy cloak and dagger conspiracy among the ministers of Earth's home government which ends up taking over the book. I think if Asimov had stuck with one or maybe two of these plots it would have been a lot better, but with four it kind of turns into a jumbled mess.

The only other complaint I could think to make is the book feels very much like it was written in the 1950's with the mores of the time period, but there's not really a lot we can do about that. It's okay, I just think it could have used a bit tighter focus.

- Kalpar

Thursday, May 4, 2017

Proven Guilty, by Jim Butcher

Today I'm looking at the eighth book in the Dresden Files series. Wait, eighth? Really? I'm eight books into this series? How the heck did that happen?

Anyway, so by now we're all fairly familiar with Harry and Butcher isn't so much building his universe as expanding within it and building upon preexisting storylines, which I greatly appreciate in a multi-book series. I remember mentioning in earlier books that it was kind of weird to me that Butcher kept introducing new elements, sometimes without much warning. But now I feel like I have a better understanding of what's going on and I'm enjoying it a lot more.

Dear and gentle readers, as this is the eighth book in a series with ongoing plotlines it is difficult for me to adequately discuss it without mentioning some spoilers. If you would like to avoid this please leave the blog now.

As with most of the Dresden books, there are a couple of things going on at once that end up connected towards the end of the book, although I feel like this connection is somewhat stronger than say, for example, Death Masks. First we see that the White Council, which was badly bloodied in the last book, dealing with the problems of being stretched thinner than ever. Harry is forced to attend the execution of a teenage boy from Korea who had fallen prey to the temptation of dark magic and had become completely twisted himself. As Harry muses repeatedly through the book, it just shows that the White Council isn't finding enough of the kids with magical talent soon enough to keep them from turning to black magic, at a time when they need every potential wizard they can get.

Ebenezer McCoy, Harry's old mentor, also asks Harry to investigate into why the fairy courts, whose territory was violated by the Red Vampire Court, had not responded to their invasion. As Harry investigates he learns that Mab, the Winter Queen, has been acting erratically which has not only set the Summer Court on the defensive, pinning their forces and making them unable to attack the Red Court, but her behavior is causing some concern among the Winter Court as well. Over the book we get hints that something far more serious is going on which (hopefully) will be explored in further books.

The biggest plot concerns Molly Carpenter, Michael and Charity's oldest daughter, who calls Harry from a police station asking him to bail her out. It turns out that Molly had dropped out of school and run away from home, joining her friends at SPLATTERCON!!!, a massive horror film convention going on in Chicago. Molly brings Harry in because some people are getting hurt or dying in mysterious ways and she thinks magic might be involved. Harry quickly determines some seriously bad magic is going down and he has to stop it before more people get killed. Eventually it turns out Molly's been involved and through Dresden's intercession with the White Council, he ends up saving her life and becoming her teacher.

As with a lot of these books, there are some things I like and some things I don't like, but it seems to balance out in the end. On the one hand, I find myself calling Harry an idiot for numerous reasons, such as his refusal to talk to Michael about his problems with Lasciel and the blackened denarius. (Of course he finally comes clean with Michael and Michael reveals he knew all along, which frustrated me on some level.) That and his tendency to go off half-cocked into things leaves me wondering if Thomas is the one using the family brain cell that week. I'm also wondering at the wheels-within-wheels-within-wheels plot that we're getting peeks of behind everything that's been going on for the past several years with Harry, suggesting much larger forces are at play. On the one hand, it's a great way to tie the series together, on the other hand, I'm left worried whether it will fit together as well as Butcher hopes it will.

My issues aside, there are plenty of things I enjoyed in this book. Harry's dog Mouse, for example, who is apparently as some sort of magic, evil-detecting tank of a dog. And I'm quite fond of dogs in the first place, so it's hardly a surprise. I also like Harry and company gearing up in steel mail and with steel weapons to invade Fairy, although I'd have recommended taking a steel tank along as well, just for good measure. And we get to see Harry be a decent person, protecting Molly from a summary execution by the White Council and outmaneuvering the Merlin to save his friend's daughter. Sometimes we don't always see Harry being what we might call a straight good guy, but this definitely makes up for it.

So overall, the book was enjoyable. If there's one thing I've found it's that these books are fun to listen to. If you're this far in the series you're probably already a fan and will look forward to more of Harry's adventures as the books continue.

- Kalpar

Anyway, so by now we're all fairly familiar with Harry and Butcher isn't so much building his universe as expanding within it and building upon preexisting storylines, which I greatly appreciate in a multi-book series. I remember mentioning in earlier books that it was kind of weird to me that Butcher kept introducing new elements, sometimes without much warning. But now I feel like I have a better understanding of what's going on and I'm enjoying it a lot more.

Dear and gentle readers, as this is the eighth book in a series with ongoing plotlines it is difficult for me to adequately discuss it without mentioning some spoilers. If you would like to avoid this please leave the blog now.

As with most of the Dresden books, there are a couple of things going on at once that end up connected towards the end of the book, although I feel like this connection is somewhat stronger than say, for example, Death Masks. First we see that the White Council, which was badly bloodied in the last book, dealing with the problems of being stretched thinner than ever. Harry is forced to attend the execution of a teenage boy from Korea who had fallen prey to the temptation of dark magic and had become completely twisted himself. As Harry muses repeatedly through the book, it just shows that the White Council isn't finding enough of the kids with magical talent soon enough to keep them from turning to black magic, at a time when they need every potential wizard they can get.

Ebenezer McCoy, Harry's old mentor, also asks Harry to investigate into why the fairy courts, whose territory was violated by the Red Vampire Court, had not responded to their invasion. As Harry investigates he learns that Mab, the Winter Queen, has been acting erratically which has not only set the Summer Court on the defensive, pinning their forces and making them unable to attack the Red Court, but her behavior is causing some concern among the Winter Court as well. Over the book we get hints that something far more serious is going on which (hopefully) will be explored in further books.

The biggest plot concerns Molly Carpenter, Michael and Charity's oldest daughter, who calls Harry from a police station asking him to bail her out. It turns out that Molly had dropped out of school and run away from home, joining her friends at SPLATTERCON!!!, a massive horror film convention going on in Chicago. Molly brings Harry in because some people are getting hurt or dying in mysterious ways and she thinks magic might be involved. Harry quickly determines some seriously bad magic is going down and he has to stop it before more people get killed. Eventually it turns out Molly's been involved and through Dresden's intercession with the White Council, he ends up saving her life and becoming her teacher.

As with a lot of these books, there are some things I like and some things I don't like, but it seems to balance out in the end. On the one hand, I find myself calling Harry an idiot for numerous reasons, such as his refusal to talk to Michael about his problems with Lasciel and the blackened denarius. (Of course he finally comes clean with Michael and Michael reveals he knew all along, which frustrated me on some level.) That and his tendency to go off half-cocked into things leaves me wondering if Thomas is the one using the family brain cell that week. I'm also wondering at the wheels-within-wheels-within-wheels plot that we're getting peeks of behind everything that's been going on for the past several years with Harry, suggesting much larger forces are at play. On the one hand, it's a great way to tie the series together, on the other hand, I'm left worried whether it will fit together as well as Butcher hopes it will.

My issues aside, there are plenty of things I enjoyed in this book. Harry's dog Mouse, for example, who is apparently as some sort of magic, evil-detecting tank of a dog. And I'm quite fond of dogs in the first place, so it's hardly a surprise. I also like Harry and company gearing up in steel mail and with steel weapons to invade Fairy, although I'd have recommended taking a steel tank along as well, just for good measure. And we get to see Harry be a decent person, protecting Molly from a summary execution by the White Council and outmaneuvering the Merlin to save his friend's daughter. Sometimes we don't always see Harry being what we might call a straight good guy, but this definitely makes up for it.

So overall, the book was enjoyable. If there's one thing I've found it's that these books are fun to listen to. If you're this far in the series you're probably already a fan and will look forward to more of Harry's adventures as the books continue.

- Kalpar

Tuesday, May 2, 2017

Arthur, by Stephen R. Lawhead

Today I'm looking at the third and what, according to my research anyway, was supposed to be the final book in the Pendragon Cycle, Arthur. This book finally gets to the reign of King Arthur, which is at least what I've been waiting for this entire time and as I said I felt like the series was building up to this. The book is told from three perspectives, by Pelleas Merlin's servant and companion, and by Bedwyr (aka Bedivere) one of Arthur's knights, both of which are set early in Arthur's reign. The final section is told from the perspective of Aneirin, a page and fosterling of Arthur well into Arthur's reign and is present at the very end. The book therefore covers the entirety of Arthur's reign but since the first two sections deal with the very early years the latter part feels very rushed.

We join Arthur when he is a mere fifteen years old and led by Merlin to London so he can retrieve the Sword of Britain from the stone where Merlin placed it. As Arthur is the rightful heir to the high kingship of Britain he has no trouble pulling the sword out. (After all, we know how the story's supposed to go.) But Arthur is not immediately recognized by the petty kings of Britain and some demand further proof of Arthur's right to kingship. After some deliberation it is decided not to grant Arthur, who is after all fifteen, the high kingship but the largely meaningless title of Dux Britanorum and the duty of protecting all of Britain from the Saxons, Picts, Irish, Angles, Jutes, Scots, Picts, and other barbarian tribes that have been raiding and invading Britain.

Over a period of years Arthur is ultimately successful in defeating not only the barbarian invaders, but also in crushing the final pockets of rebellion among the British lords, some of whom decide working with the barbarians is better than swearing fealty to Arthur. Arthur marries Guinevere, and a new period of peace and prosperity begins in Britain. Of course eventually a Mordred character shows up, although the weird thing is he isn't actually Arthur's son. He's still Morgan's son and is clearly there to ruin everything for Arthur and Britain, but he doesn't seem to worm his way into Arthur's court and causes trouble. Morgan gets caught by one of Arthur's knights and executed, and Mordred immediately runs away, swearing he'll get his revenge.

Arthur's downfall is caused largely through his own hubris. Arthur has himself crowned emperor in the west, which results in the Byzantine emperor immediately saying Arthur can't truly call himself emperor in the west if he hasn't liberated Rome from the barbarians. Despite Merlin saying mounting a campaign to liberate Rome is a bad idea, Arthur decides to do so anyway and leaves with most of his soldiers. Mordred immediately gets the Picts to rise in rebellion and sacks Arthur's capital, taking Guinevere and Merlin hostage. Arthur has to come back and engages Mordred and his followers in combat. As anyone who knows the Arthurian myth knows, many of Arthur's best knights are killed, Arthur slays Mordred, but not before Mordred fatally wounds Arthur. Merlin then takes Arthur to the isle of Avalon with the fair folk (The survivors of Atlantis who have been hanging around) and they then disappear off the face of the earth.

There is one thing that I can appreciate about this book and it's the effort on the part of the author to include some of the older knights in the mythos such as Kay, Bedivere, and Bors and completely excluding Lancelot who is a later addition to Arthurian lore. As I mentioned in my review of Gwenhwyfar, it's kind of weird to see Lancelot in a semi-historical retelling of Arthur because he was basically grafted onto the story later. So on that level I really appreciated the exclusion of Lancelot from the story.

That being said, there are a lot of problems with this book and I'm almost left with the feeling that Lawhead wasn't entirely sure what he wanted to do with the story. At one point Merlin is blinded by Morgan after engaging in a magical battle with her. Merlin is not only blinded physically but also magically and is no longer able to determine the shape of future events. I was left with the feeling this was a permanent change to Merlin and Lawhead's way of making Merlin less powerful and less able to aid Arthur in years to come. However, when we jump ahead to the final third of the book, Merlin has his sight again, both literally and metaphorically. So it felt like there weren't really any consequences for Merlin.

I also didn't understand the decision to make Mordred not related to Arthur, especially after Lawhead incorporated a prophecy Guinevere heard where Arthur's son would kill him so Guinevere has been taking efforts to avoid conceiving a child with Arthur. Granted this information is coming from Morgan and Merlin immediately dismisses everything she says as lies, but Guinevere certainly reacted as if what Morgan was saying was the truth. But Lawhead then turns around and has Merlin say that Mordred's father is one of Morgan's children through Lot of Orkney. Assuming Merlin is correct, then why even mention the prophecy? The prophecy exists to create a Mordred-shaped hole in the narrative for him to slip into. If Mordred isn't Arthur's son and is just some guy, why even include the prophecy? It just doesn't make a lot of sense to me.

Another thing I didn't quite understand was how the Grail Quest was included. Lawhead has taken a very pro-Christianity stance throughout these books and he went through the effort of making the Fisher King, a prominent figure in Grail lore, not only a main character but also Merlin's grandfather. You would think that the Grail Quest would be central to Lawhead's story of Arthur's reign but it's mentioned exactly twice. Once, when the quest is first given and Arthur announces they have been chosen by God to seek the Holy Grail. At which point it's immediately forgotten because Arthur wants to crown himself emperor and another emperor said he isn't really an emperor if he doesn't control Rome. The Grail Quest is only mentioned again in a post script where the narrator basically says, ''Oh yeah, after Arthur disappeared, some of his knights went to find the Grail which we forgot about. They didn't succeed.'' So I'm puzzled by Lawhead's decision. He went through so much effort to include Christianity and the Fisher King and when it comes for the most Christian quest of all, he totally drops the ball on it. I assume it's covered in more detail in the next books, Pendragon and Grail, but I honestly can't say I'm really interested in reading it.

Overall this book feels like a lot of missed opportunities or confusion. Lawhead's obviously making an attempt to include older parts of the Arthurian mythos but the result feels inconsistent or incomplete. And for whatever reason, the Grail Quest, which should have been the centerpiece, is almost entirely forgotten. And with Arthur gone, with no heir and Britain falling to barbarian invaders, I'm not sure where the series can go from here. I'll probably look at the summary of Pendragon and make a decision, but I'm not sure if I want to keep with this particular Arhturian re-telling.

- Kalpar

We join Arthur when he is a mere fifteen years old and led by Merlin to London so he can retrieve the Sword of Britain from the stone where Merlin placed it. As Arthur is the rightful heir to the high kingship of Britain he has no trouble pulling the sword out. (After all, we know how the story's supposed to go.) But Arthur is not immediately recognized by the petty kings of Britain and some demand further proof of Arthur's right to kingship. After some deliberation it is decided not to grant Arthur, who is after all fifteen, the high kingship but the largely meaningless title of Dux Britanorum and the duty of protecting all of Britain from the Saxons, Picts, Irish, Angles, Jutes, Scots, Picts, and other barbarian tribes that have been raiding and invading Britain.

Over a period of years Arthur is ultimately successful in defeating not only the barbarian invaders, but also in crushing the final pockets of rebellion among the British lords, some of whom decide working with the barbarians is better than swearing fealty to Arthur. Arthur marries Guinevere, and a new period of peace and prosperity begins in Britain. Of course eventually a Mordred character shows up, although the weird thing is he isn't actually Arthur's son. He's still Morgan's son and is clearly there to ruin everything for Arthur and Britain, but he doesn't seem to worm his way into Arthur's court and causes trouble. Morgan gets caught by one of Arthur's knights and executed, and Mordred immediately runs away, swearing he'll get his revenge.

Arthur's downfall is caused largely through his own hubris. Arthur has himself crowned emperor in the west, which results in the Byzantine emperor immediately saying Arthur can't truly call himself emperor in the west if he hasn't liberated Rome from the barbarians. Despite Merlin saying mounting a campaign to liberate Rome is a bad idea, Arthur decides to do so anyway and leaves with most of his soldiers. Mordred immediately gets the Picts to rise in rebellion and sacks Arthur's capital, taking Guinevere and Merlin hostage. Arthur has to come back and engages Mordred and his followers in combat. As anyone who knows the Arthurian myth knows, many of Arthur's best knights are killed, Arthur slays Mordred, but not before Mordred fatally wounds Arthur. Merlin then takes Arthur to the isle of Avalon with the fair folk (The survivors of Atlantis who have been hanging around) and they then disappear off the face of the earth.

There is one thing that I can appreciate about this book and it's the effort on the part of the author to include some of the older knights in the mythos such as Kay, Bedivere, and Bors and completely excluding Lancelot who is a later addition to Arthurian lore. As I mentioned in my review of Gwenhwyfar, it's kind of weird to see Lancelot in a semi-historical retelling of Arthur because he was basically grafted onto the story later. So on that level I really appreciated the exclusion of Lancelot from the story.

That being said, there are a lot of problems with this book and I'm almost left with the feeling that Lawhead wasn't entirely sure what he wanted to do with the story. At one point Merlin is blinded by Morgan after engaging in a magical battle with her. Merlin is not only blinded physically but also magically and is no longer able to determine the shape of future events. I was left with the feeling this was a permanent change to Merlin and Lawhead's way of making Merlin less powerful and less able to aid Arthur in years to come. However, when we jump ahead to the final third of the book, Merlin has his sight again, both literally and metaphorically. So it felt like there weren't really any consequences for Merlin.

I also didn't understand the decision to make Mordred not related to Arthur, especially after Lawhead incorporated a prophecy Guinevere heard where Arthur's son would kill him so Guinevere has been taking efforts to avoid conceiving a child with Arthur. Granted this information is coming from Morgan and Merlin immediately dismisses everything she says as lies, but Guinevere certainly reacted as if what Morgan was saying was the truth. But Lawhead then turns around and has Merlin say that Mordred's father is one of Morgan's children through Lot of Orkney. Assuming Merlin is correct, then why even mention the prophecy? The prophecy exists to create a Mordred-shaped hole in the narrative for him to slip into. If Mordred isn't Arthur's son and is just some guy, why even include the prophecy? It just doesn't make a lot of sense to me.

Another thing I didn't quite understand was how the Grail Quest was included. Lawhead has taken a very pro-Christianity stance throughout these books and he went through the effort of making the Fisher King, a prominent figure in Grail lore, not only a main character but also Merlin's grandfather. You would think that the Grail Quest would be central to Lawhead's story of Arthur's reign but it's mentioned exactly twice. Once, when the quest is first given and Arthur announces they have been chosen by God to seek the Holy Grail. At which point it's immediately forgotten because Arthur wants to crown himself emperor and another emperor said he isn't really an emperor if he doesn't control Rome. The Grail Quest is only mentioned again in a post script where the narrator basically says, ''Oh yeah, after Arthur disappeared, some of his knights went to find the Grail which we forgot about. They didn't succeed.'' So I'm puzzled by Lawhead's decision. He went through so much effort to include Christianity and the Fisher King and when it comes for the most Christian quest of all, he totally drops the ball on it. I assume it's covered in more detail in the next books, Pendragon and Grail, but I honestly can't say I'm really interested in reading it.

Overall this book feels like a lot of missed opportunities or confusion. Lawhead's obviously making an attempt to include older parts of the Arthurian mythos but the result feels inconsistent or incomplete. And for whatever reason, the Grail Quest, which should have been the centerpiece, is almost entirely forgotten. And with Arthur gone, with no heir and Britain falling to barbarian invaders, I'm not sure where the series can go from here. I'll probably look at the summary of Pendragon and make a decision, but I'm not sure if I want to keep with this particular Arhturian re-telling.

- Kalpar

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)